Art reflecting Life

Addiction and reverse addiction in film

It always amazes me when I see art reflecting the deeper things in life, particularly in film. Patterns and themes that can often take therapists years to learn and recognise are often portrayed by artists with no training or apparent expertise. These themes and traits are often included in their work primarily as observations from the life of the artist themselves and are all the stronger for that. In this post I am going to take a look at the main theme of my work, which is the family pattern of addiction and reverse addiction. And the way I see this reflected in storylines of Films and TV series. Particularly in the way people caught in this pattern, attract each other, live with each other, affect each other and frustrate each other.

Addiction and reverse addiction as relationship patterns

Years before my own recovery, it was obvious to me that certain people would react to me more favourably than others. Whilst some would clearly be affected by some form of empathy around my ‘problems’, others would be unaffected (I thought they were cold) and would say I had a ‘chip on my shoulder’. I also noticed a tendency to ‘flip’ or change my personality depending on who I was with. When I was with someone who was very giving and generous, I would tend to take advantage, whilst also developing a state of hoplessness. On the other hand, when with people who acted more selfishly, I noticed a tendency to feel responsible for their welfare, even down to shopping, cooking and cleaning

Although I did not understand it yet, and was still some years away from my own recovery, I was experiencing part of the pattern of addiction and reverse addiction. Years later, after I had recovered from my own addiction, I studied and became a therapist. This led me to an understanding of narcissistic tendency and co-dependence as medical terms. However, being trained as a systemic therapist, I did not see these things as conditions. Instead, I learned to use communication theory as a way of recognising patterns and themes around the way people engage in relationships.

Moving away from simple medical diagnosis

Using my own experience as well as my training, I learned to see issues as things co-created in relationships, rather than immutable personal traits or conditions. In other words, that the way we are is, at least partly, contingent on who we are with. It is from this perspective that we can relate the positions of addiction and reverse addiction more closely together. As opposed to unrelated ‘conditions’ such as addiction and codependency.

As I started to develop these ideas in my practice and rehabs I worked in, I started to notice a great deal of consistency in the way people were attracted or repelled by each other. So this started to make sense to me based upon their history and tendency. For instance, an addict that had been extreme in their behaviour will tend to attract an extreme reverse addict. Whilst a more high functioning addict who has no history of drifting into chaos, will tend to attract someone with a milder form of reverse tendency. In other words, there is a form of unhealthy balance here which is unconscious but extremely consistent.

My main aim in this post is to look at the examples of this pattern in film and TV. There are many examples so I will restrict myself to three, one film, one TV series and one book. Finally I will look at the greatest example the world has been given, which is the story of the Prodigal from Luke 15 in the Bible. The purpose of introducing these ideas through mainstream media projects is to help you to see the patterns more clearly for yourself, and to use this understanding in your own recovery. There is no better way to gain a better understanding of something than to see it as part of a story. Let’s first look at a very current series Happy Valley, with the amazing Sarah Lancashire and Siobhan Finneran.

The purpose of introducing these ideas through mainstream media projects is to help you to see the patterns more clearly for yourself

Happy Valley

The pattern of addiction and reverse addiction is strongly present in the BBC series Happy Valley. There have been two seasons already produced with a third due to be aired on January the 1st. In the story Catherine Cawood (played by Sarah Lancashire) is a Police Sergeant in a small Yorkshire Town. Her Sister Clare (played by Siobhan Finneran), lives with her along with her grandson Ryan (played by Rhys Connah).

Initially not much is made of Clare’s addiction, it’s only later in the series (series two, episode two) that the complexity of the sisters relationship is exposed through the vulnerability of Clare when she is left at a funeral by Catherine for several hours. She gets drunk with the daughter of the deceased Anne Gallagher (played by Charlie Murphy) who is also alcoholic. This begins yet another chaotic night

Components of the theme

There are many recognisable components of the above mentioned theme present in this series. Notice that when Clare gets drunk, it is when she is left for five hours at a funeral because Catherine is so busy trying to meet many other obligations. This weight of responsibility for others, felt by the ‘reverse tendency’ is a strong component of the theme and one of the main ways that reverse addicts become burned out. There often seems to be no defence for the reverse addict against the consistent needs/demands of the addict., and the continual pressure of meeting others needs.

Familial construction

This pattern is primarily seen inside a family and we always remember that Catherine and Clares attitudes were both born out of the same family, the same parents, the same upbringing. Any dysfunction in the family tends to pressurise the children into one or other of these extreme patterns. The interesting thing is why do people in the same family tend to go in apparently opposite directions? Whilst Clare became a heroin addict and did not manage to make any progress in her career, Catherine grew up with the huge burden of responsibility for others. This led to a career in the Police force and an unhealthy pressure of responsibility to be looking after others.

In the series Catherine is holding down a difficult Police Seargents role in a small Yorkshire Town. Underfunded and unsupported from upstream, she has chosen to step back from her detectives role in order to look after her Grandson. Left when her daughter commited suicide. She is also housing her sister Clare who is volunteering locally but not yet secure in her recovery. You might ask, “who made Catherine responsible for everyone else”? What makes Clare sometimes give up on everything and return to the drugs whilst her sister cannot leave her post? It is this bifurcation along family lines that is not natural, they were not born this way. It is the effect of dysfunction in the family.

Relationship construction

How we build relationships, and who we build them with, form another strong theme. Addicts and reverse addicts are like magnets, forming very strong attractions and repulsions. Because of the subconscious nature of this attraction, the unhealthy aspects of the bond are often not apparent until much later. If you ask someone who struggles with these things why they do what they do, they will often answer vaguely or with a somewhat glib reply. Those of you who have watched the series will see this in Catherines responses. The moral sense that they are supposed to do something is a force that is present in the brain more than the mind and, as such, is not easy to get to grips with. The good news is that the brain can be rewired.

It’s also important to review how you think about yourself. If your thinking is built on ideas like “I’m like this” or “I’m too much like that”, then there isn’t much you can do. However, if you can start to think of relationships as the way of understanding yourself, then you are opening up all kinds of possibilities for growth and development. Think about who you are in this, or that relationship, and why. It’s very noticable in this series that Catherine is very different depending on who she is with.

The moral sense that they are supposed to do something is a force that is present in the brain more than the mind and, as such, is not easy to get to grips with.

Intensity explosions

Explosions often become inevitable in the intensity of such unhealthy, unbalanced relationships such as the Sisters in this series. What the reverse addict sees as caring, helpful and necessary, the addict eventually experiences as restricting, smothering and controlling. Notice in the drinking scene how Clare is desperate for Catherine to “leave her alone”. This pattern or theme naturally strangulates over time to become an unbearable tension for both. The more the reverse addict notices the addict’s problems, the more they act to help. The more the addict perceives the help as controlling, the more they attempt to be free of it, and so on.

Flipping as a relational phenomenon

Following the intensity of the explosion in the relationship, the typical way Catherine and Clare relate is itself reversed, in other words they can ‘flip’ or swap positions. It is part of the pressure of the unhealthy balance. So, following the explosion we would tend to see reflection on behaviour. The addict might be concerned about the extent of their selfishness, the reverse addict eventually cracks under the pressure of meeting everyone else’s needs. Flipping then, is something that happens not only within an intense relationship but also, as a natural consequence of who we engage with.

Only when I laugh

In the 1981 film “only when I laugh” adapted from the play of the same name by Neil Simon, Georgia Heinz (played by Marsha Mason) is recovering from alcoholism. The story covers Georgia’s return from rehab and her attempts to return to her acting career. There are many great observations in this piece and several themes are present.

Notice in this clip from the movie, how the friend and the daughter go from lively animated chatter to a kind of limp lifeless silence once Georgia has left the room.

It was fascinating to me that in her interview with Bobbie Wygant Marsha confirms that she did not have alcoholism in the family, but had seen people who did not realise that they were embarrassing themselves with alcohol. Neil Simon grew up during the great depression and was said to have had a volatile upbringing with the family splitting up several times, but alcohol l was not the problem. So, again, they were derived from observation and human understanding.

Far from the madding crowd

I can’t finish this brief look at these patterns and themes without a mention of Mark Clark. A character most of us can recognise in our lives. In Thomas Hardy’s novel Far from the madding crowd, he introduces the character briefly.

“True, true; it can’t be gainsaid!” observed a brisk young man–Mark Clark by name, a genial and pleasant gentleman, whom to meet anywhere in your travels was to know, to know was to drink with, and to drink with was, unfortunately, to pay for.

In Hardy’s novel this character is portrayed as somewhat more universal, as if he would have the same effect on everyone. And there are some that appear to have this effect, but most people have different effects on different people.

The Prodigal.

The greatest example of this family pattern comes from the Bible and is found in the Gospel of Luke. In Chapter fifteen we read the story of the Prodigal Son. Possibly the most famous story in the Bible. Along with Noah and the flood, Adam and Eve in the garden, the Prodigal is so well known that people of all faiths and no faith are familiar with it.

Of course the typical way this story is taught and understood is in the context of the Fathers love for his sons, and this is clearly the main idea, but there is another underlying theme here and it is so important that when I am teaching counsellors and Church leaders about how to help people in their recoveries, I say that everything we need to know about addiction, rock bottoms and recovery is in this story! It’s all there if we dig a little deeper.

So we see all the usual suspects in this tale. Isolation, selfishness, poor decisions, chaotic behaviour and wild living. Rock bottoms and repentance. Acceptance and reconciliation. But wait! There is also another theme emerging right at the end! Look at the way the older son is so angry at the reconciliation that he refuses to go into the house. The Father goes out to him but he will not be comforted. This issue is so serious that we do not even see the resolution of it in the story.

Learning from our greatest teacher

Well, what is the older brother’s complaint? What is the problem? Shouldn’t he be happy that his younger Brother is back in the family? Well, if all his work, contributions and commitment were genuine, he would be. But his issue is exposed right at the end of the story when he cannot contain his resentment. He did not get the outcome all his efforts were aimed at. So here it is again. Two siblings from the same family, with the same Father, the same environment and the same history. And yet they grow up in completely opposite ways! One trys to gain acceptance and success by following all the apparent rules and meeting everyones expectations. Whilst the other escapes into selfishness and thinks only about what he can get! Looking at this story again through this apparently ‘modern’ lens is fascinating. It shows us that this family pattern has been around forever and will continue to emerge wherever families are formed.

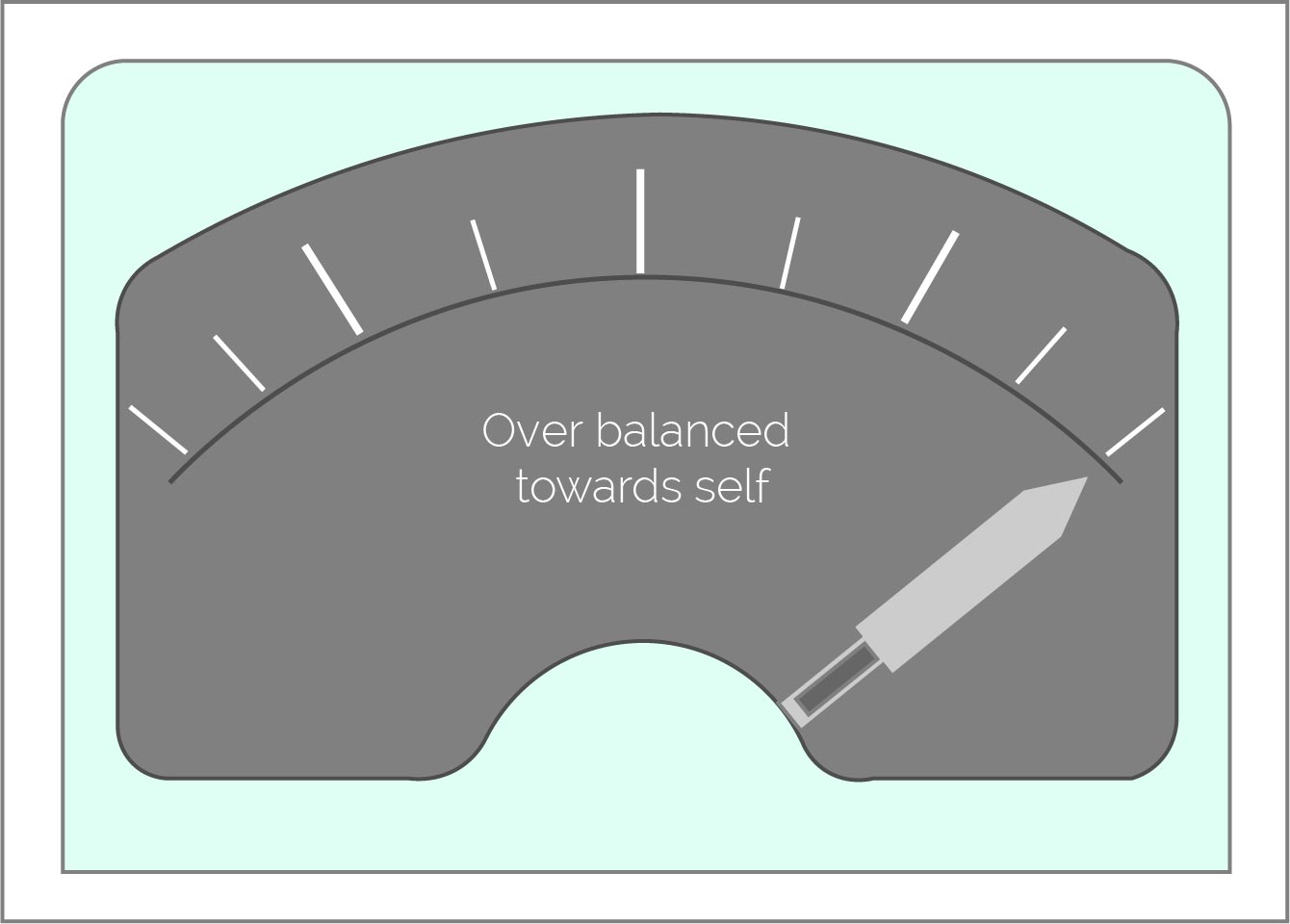

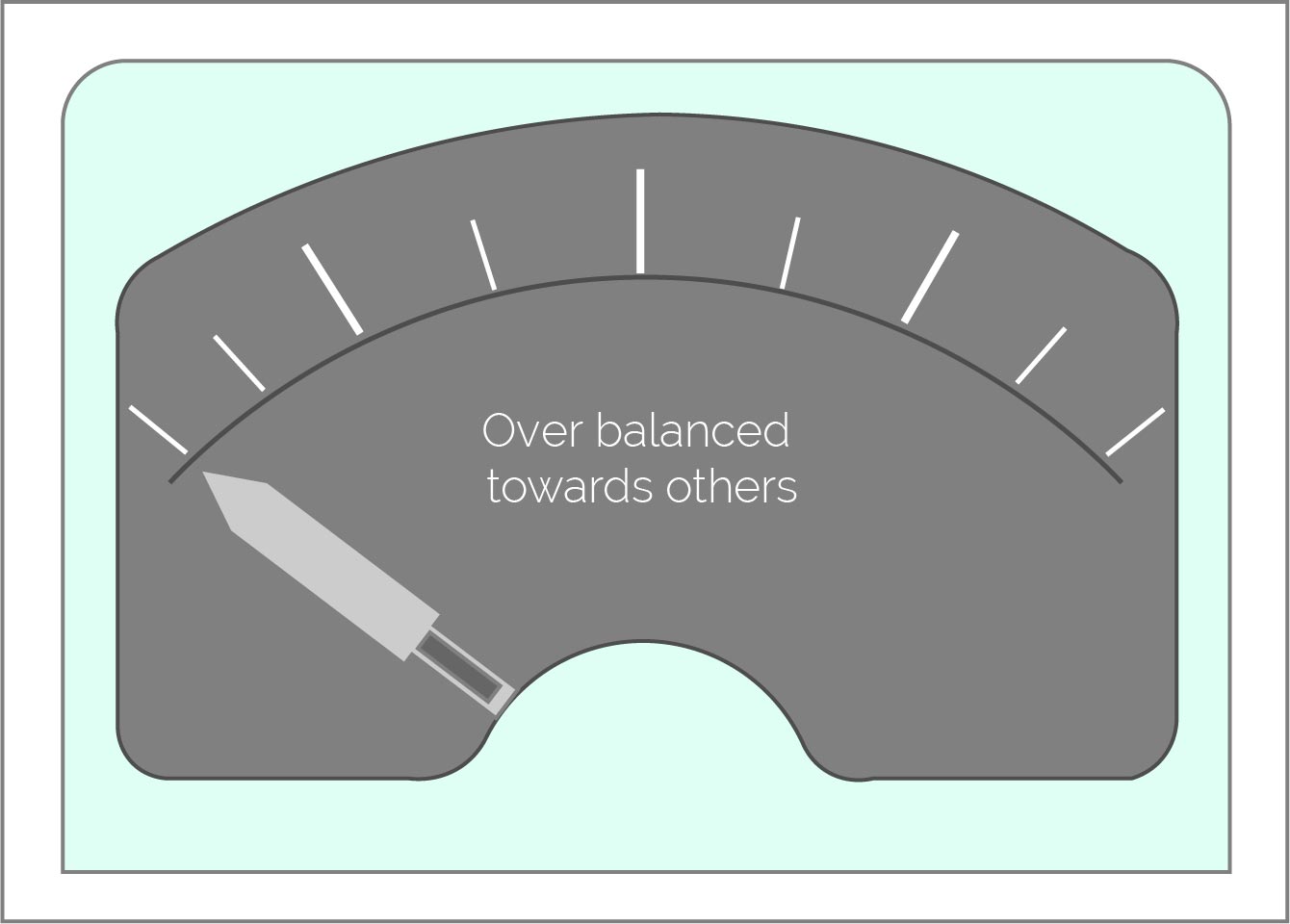

I really hope that this brief journey into art and the way it has reflected life has given you some food for thought, Especially if this is a subject you are struggling with yourself. Our aim in recovery is to improve all our relationships. With everything, and everybody! This means achieving a balanced position in relation to our boundaries with others. This can be very difficult and take time, so be patient with yourself. Take another look at this post for guidance on balance and what it looks like.

Thanks again for taking the time to read this. All the best with your progress.

When you become dependent or addicted to something you have entered a trap. Everyone would recognise that, but what kind of trap is it? The basic understanding of the trap is that you have started doing something or taking something that is ‘addictive’. In other words the thing itself has the quality of addictiveness. Have you heard yourself say “that thing is soooo addictive”. There is no doubt that things, particularly things that have been designed as such, like cigarettes and internet gaming are ‘moreish’. One of the biggest, television, has had us as a culture for a long time.

When you become dependent or addicted to something you have entered a trap. Everyone would recognise that, but what kind of trap is it? The basic understanding of the trap is that you have started doing something or taking something that is ‘addictive’. In other words the thing itself has the quality of addictiveness. Have you heard yourself say “that thing is soooo addictive”. There is no doubt that things, particularly things that have been designed as such, like cigarettes and internet gaming are ‘moreish’. One of the biggest, television, has had us as a culture for a long time.  it is at this point that the problem becomes very real. The addictive trap is not really ‘felt’ until the solution to your problem becomes the very thing that produced the problem in the first place! This brings us to one of the best definitions of addiction.

it is at this point that the problem becomes very real. The addictive trap is not really ‘felt’ until the solution to your problem becomes the very thing that produced the problem in the first place! This brings us to one of the best definitions of addiction.  I had to learn to

I had to learn to

Of course we remain in relationship with loved ones even after we lose them and, as previously mentioned, seems like we are in relationship with everything, living and dead. Your problem is not that you are in a relationship. The person who does not drink at all is still in relationship with alcohol. The person who never gambles is still in a relationship with gambling. So your problem is the depth at which you have bonded with this behaviour or substance. If you are a person with an addictive personality there is every chance that your relationship with this substance should include a firm boundary that dictates never using it. Similar to the boundary we have around never touching poison.

Of course we remain in relationship with loved ones even after we lose them and, as previously mentioned, seems like we are in relationship with everything, living and dead. Your problem is not that you are in a relationship. The person who does not drink at all is still in relationship with alcohol. The person who never gambles is still in a relationship with gambling. So your problem is the depth at which you have bonded with this behaviour or substance. If you are a person with an addictive personality there is every chance that your relationship with this substance should include a firm boundary that dictates never using it. Similar to the boundary we have around never touching poison.

The Relational View of recovery from addiction

The Relational View of recovery from addiction